By Anthony Tommasini

June 7, 2019

For 40 years the composer David Lang had toyed with writing his own version of Beethoven’s “Fidelio.” Why? Well, why not? It’s inspiring when a living composer, rather than being intimidated by the work of a past master, pays homage to it, even critiques it, by writing a contemporary version.

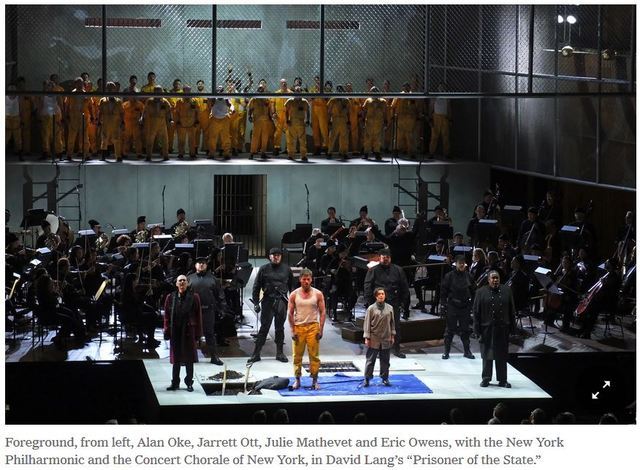

That’s what Mr. Lang has done in “Prisoner of the State,” a 65-minute opera commissioned by the New York Philharmonic (and five other international institutions), which had its premiere production, directed by Elkhanah Pulitzer, on Thursday night at David Geffen Hall. An exciting performance was led by Jaap van Zweden. Though some elements in the score seem like miscalculations, “Prisoner” is a dark, seething and engrossing work.

“Fidelio” tells of a Spanish noblewoman who, disguised as a young man, has taken a lowly job at a prison where her husband is being unjustly held by a powerful political enemy. Though the score contains some of Beethoven’s most noble and beautiful music, as Mr. Lang writes in a program note, the opera is encumbered by a mistaken-identity secondary romance and stock comedic bits that undermine its themes of combating tyranny and championing freedom.

Mr. Lang streamlines the story and places it in an unspecified contemporary time. For this production, with Matt Saunders’s scenic designs, the walls of the stage were lined with barbed-wire fencing. The inmates (the impressive men of the Concert Chorale of New York), dressed in yellow jumpsuits, huddled together on an elevated platform behind the orchestra. When they rose to sing, surveillance cameras projected video images of them in triplicate. Even the Philharmonic players wore plain black clothing and knitted caps.

Mr. Lang also wrote the libretto. This may have been a mistake, or at least a lost opportunity to have a strong literary collaborator. He draws upon phrases from the librettos Beethoven went through in earlier versions of his opera, and also adapts texts from Machiavelli, Jeremy Bentham and other pertinent sources.

But there are stilted phrases in the resulting libretto, starting with the opening aria for the Assistant (the heroic wife), who at the beginning addresses the audience. “I was a woman once,” she sings; “I lived as women live/I felt as women feel.” Mr. Lang rescues these lines (and others throughout the opera that skirt platitude) through the hazy beauty and relentless drive of his music. As the Assistant, Julie Mathevet, a young, radiant soprano, conveyed both the despair and bitterness in the vocal lines, which sometimes have a jazzy cast. The orchestra cushions her in ethereal sonorities for high strings hovering over tremulous undertows flecked with soft chimes and percussion.

The Jailer (the bass-baritone Eric Owens drawing upon the most gravelly qualities of his powerful voice) arrives, sputtering commands at the prisoners amid muttered comments on the cold bleakness around him.

“Prisoner” is strongest when Mr. Lang departs the most boldly from Beethoven. In “Fidelio” the jailer, in a jocular aria, drones on to his assistant and his daughter about the importance of money to a good domestic life. For his jailer’s equivalent, “Gold,” Mr. Lang presents the character’s jaded take on life.

Without gold, power and love will be grabbed by others, he sings in pontifical vocal phrases laced with moments of subdued anxiety. The orchestra backs him up by grinding out insistent figures as other instruments needle the music with piercing dissonance.

Another moment when Mr. Lang supplies a compelling contemporary retort to Beethoven comes in an aria for the autocratic Governor (the charismatic, bright-voiced tenor Alan Oke). Love is a bond that men will break, the governor sings; but a “man who fears you will never leave your side.” The music is almost elegiacally lyrical and haunting, suggesting that this ruthless governor is just operating within the woeful confines of contemporary life as he knows it to be.

Halfway through we see the Prisoner (the muscular-voiced baritone Jarrett Ott in an anguished performance) on a surveillance video singing from his underground cell. In the climax of the opera, as the Prisoner is about to be stabbed, the Assistant draws a pistol on the Governor and shoots him.

The Governor does not die. The opera shifts into a final episode that seems a bitter antidote to the celebratory triumph that concludes “Fidelio.”

“We are born free,” everyone sings, but “are in chains.” Only in prison, though, does one see the chains. This is cynical stuff. Yet, stretches of this scene unfold in strenuous choral writing over a heaving orchestra of shifting chords to shattering effect.

Mr. Lang fearlessly explores the dark implications of this story. A gifted librettist might have better touched upon its complexities. Still, this ambitious work, which concludes the Philharmonic’s “Music of Conscience” series, is a high point of Mr. van Zweden’s first season as music director. Give him — and Deborah Borda, the orchestra’s visionary president — credit for thinking big.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/07/arts ... eview.html